Diana Nawi at The Olivia Foundation. Photo by Andy Butler.

Based in Los Angeles, curator Diana Nawi has spent the last fifteen years organizing exhibitions across the United States and internationally, moving between museums, biennials, and independent projects. Her approach is both scholarly and intuitive—one that embraces the complexity of curatorial labor while foregrounding the emotional and spatial experience of the viewer.

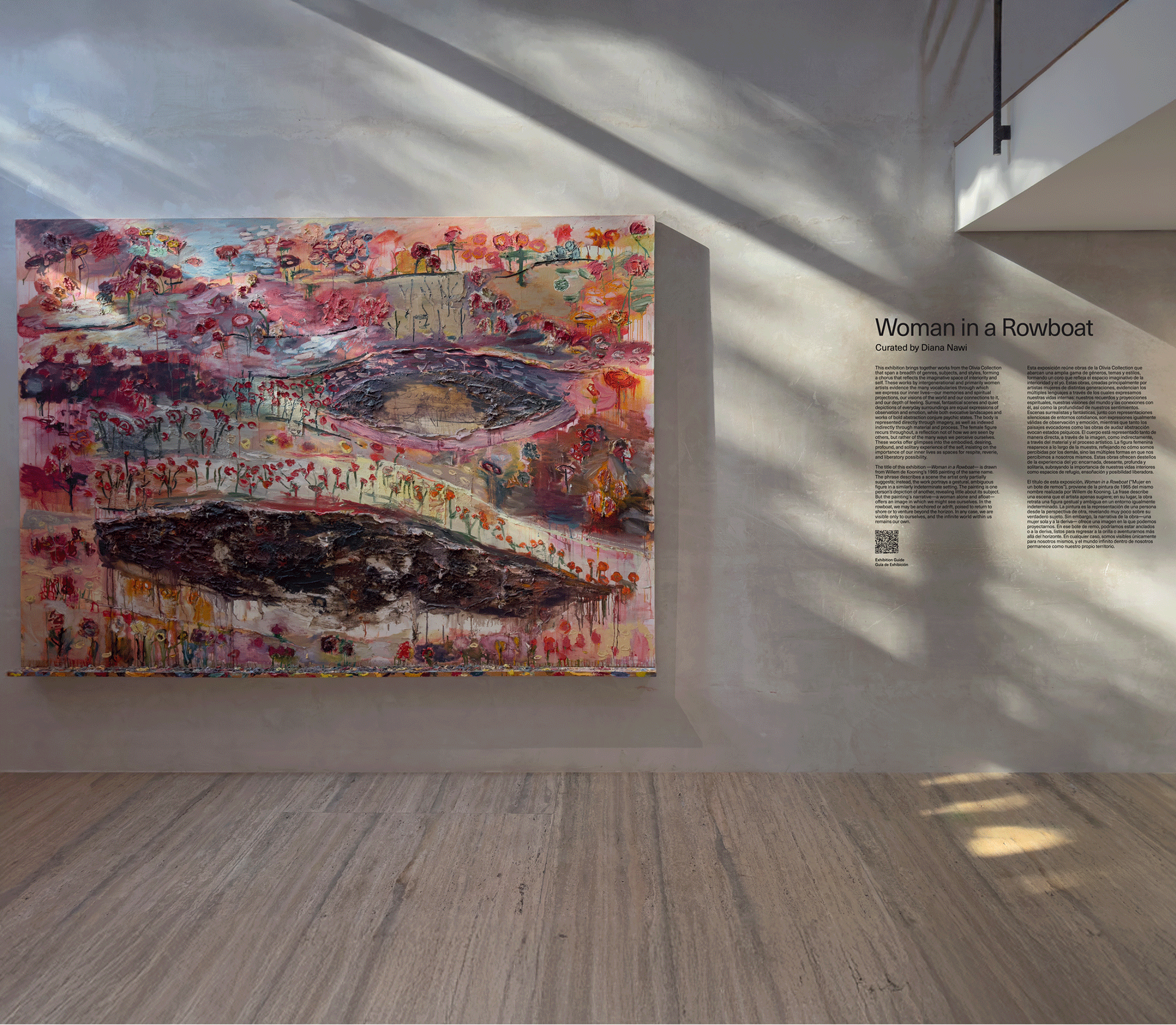

Woman in a Rowboat marks Nawi’s second exhibition with The Olivia Foundation, following Between Us, presented in 2024. For this new project, she brings together a group of works that reflect on interiority, perception, and the gaps between self-image and how one is seen. The exhibition unfolds as a nonlinear narrative, drawing out unexpected formal connections between works and inviting the visitor to navigate a choreography of visual thought. Taken together, the artworks propose an inquiry into authorship, visibility, and the limits of expression.

This conversation took place at The Olivia Foundation during the final stages of installation, as Nawi reflected on the origins of the exhibition, her curatorial philosophy, and the personal references that shaped this layered project.

Diana Nawi at The Olivia Foundation. Video by Studio Chirika.

“The curator exists somewhere between a conductor, a producer, and an art director. But ultimately, if you’re a good curator, you’re an exhibition maker.”

Can you tell us a bit about your background and curatorial practice?

My name is Diana Nawi. I’m a curator based in Los Angeles. In the last 15 years, I’ve worked all over the U.S. and a bit abroad, curating museum exhibitions, biennials, and other kinds of projects.

Curators are also logistics people. They’re scholars, they’re essayists, they’re historians, they’re administrators—they are at the nexus of creativity and administrative work. And I really think about that a lot in my work. What does it mean to actually realize something?

In particular, working on exhibitions like this, that are outside of the institutional or museum context—that are not meant to be singular, scholarly, thesis-driven exhibitions—I think the role of a curator is amplified. The curator exists somewhere between a conductor, a producer, and an art director. But ultimately, if you’re a good curator, you’re an exhibition maker. And the first thing you need to think about is: what is the visitor’s experience of this show?

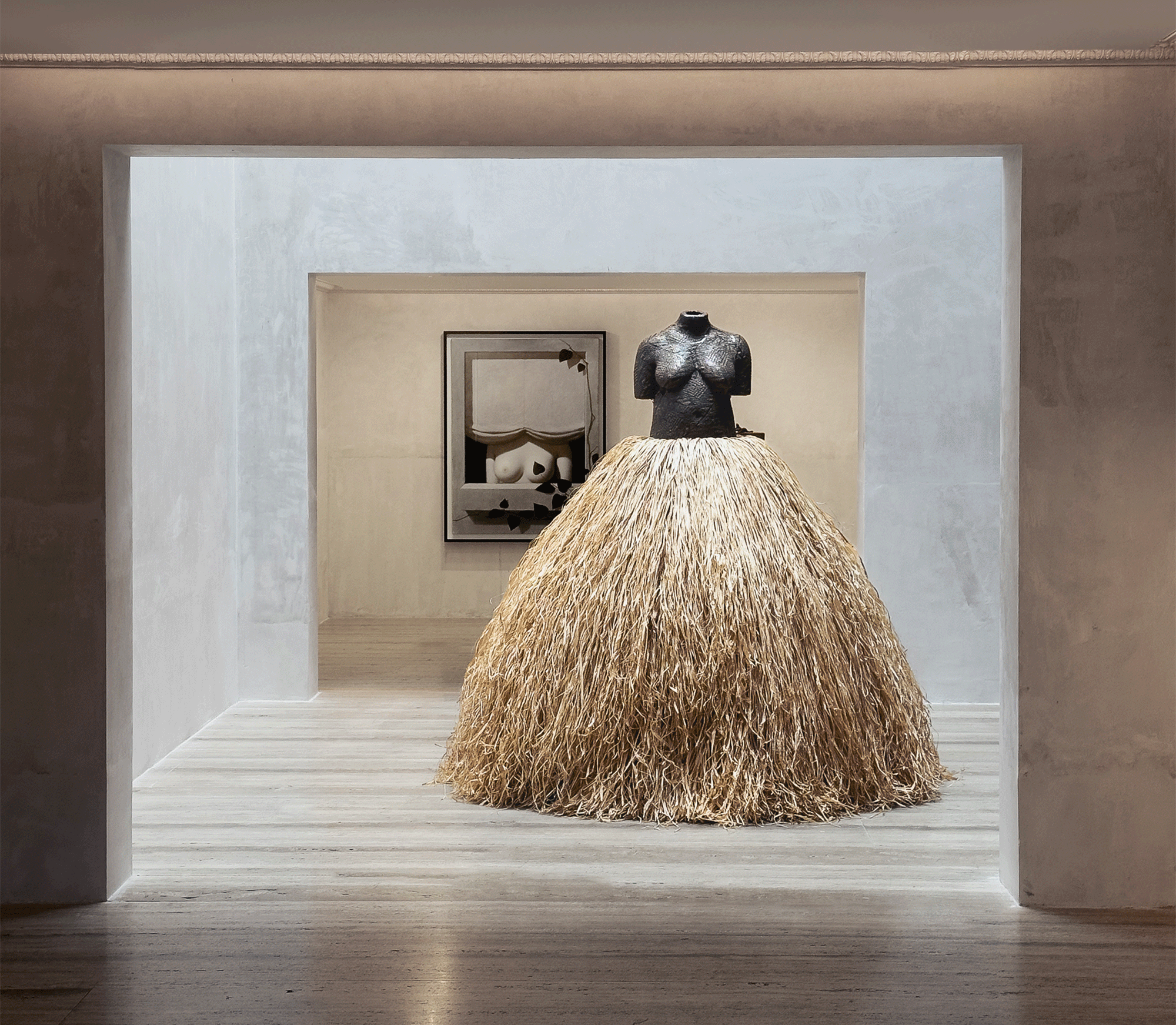

Artworks from The Olivia Collection, part of the exhibition Woman in a Rowboat. Curated by Diana Nawi. Photography by Andy Butler, Sergio López, and Studio Chirika. Courtesy of The Olivia Foundation.

The exhibition title, Woman in a Rowboat, is taken from a de Kooning painting. What drew you to that work?

The show is called Woman in a Rowboat, which is borrowed from a 1965 de Kooning painting that’s on view in the exhibition. I thought about it both because of the poetry of the title, but also because of the kind of claim it makes. [The title tells you there’s a] woman in a rowboat. So it’s a kind of very small narrative, a description. And you go to look at the painting—you can barely find the woman. There’s no rowboat. It is nothing like the image in your mind.

So there’s this idea of what we say we’re doing, what we’re actually doing, and what it means to observe someone else.

But de Kooning has this heavy baggage—this kind of misogynistic, heavy baggage—of what it is to look at a woman from outside of the picture. And I think this idea that someone is looking right at you, [but] you can’t see yourself in that image—in someone else’s image of you, you are not visible. But to yourself, there’s [a] really rich space, this infinite space inside you.

How did you approach the spatial narrative of the show?

When you’re putting an exhibition together, you are responding to two things: the work and the space. Maybe that’s an obvious thing to say, but reconciling those two is actually quite difficult. You could have a [selection] of paintings that you really want to show, but [it won’t work]—they don’t go together, they don’t work in the space.

Having [curated the exhibition here] last year, I was really thinking about how I wanted to take advantage of the architecture, to tell a story and to think about the visitors’ choreography. A show is ultimately a story, and people are moving through it—so it becomes narrative in that way.

What were some of the first works that shaped the tone of the exhibition?

The show begins with two really cacophonous works—one by John Snyder and one by Anselm Kiefer. And they’re both landscapes. Hers is this really hectic, fertile pink, gestural springtime landscape that includes, at the bottom of the work, a shelf with a palette of paint drippings. And Kiefer’s is this incredible, thick impasto fall scene of a forest.

So you already have this death-birth [dialogue] happening. You’re in the valley—very much betwixt and between spring and autumn. It is not just a picture of a landscape; it’s [also] a psychic space.

Diana Nawi at Olivia Foundation. Video by Studio Chirikia.

Can you speak about the artists in [this gallery] and how their work speaks to themes of interiority and perception?

There are only four artists in this gallery, but I think they really embody the central ideas of the exhibition.

Etel Adnan is most famous as a poet, but she made these incredible small abstractions with really elemental shapes and colors. They’re hard not to read almost as landscapes.

Then there are works by Joan Semmel, who is an artist in [her early 90s], and who has continued to paint her body over time. These two different works [one shows] a moment of turning away from the viewer—to deny the viewer access to yourself. And then you also see this painting that’s so clearly about what we see when we look at ourselves. It’s from the perspective of someone looking down at their own body, but it’s totally abstracted, surreal, grotesque [and] there are all these kind of unnatural colors.

Then there’s this incredible work by Tomm El-Saieh, a much younger artist based in Miami. Up close, you really see how much work has gone into it—how many singular gestures and moments comprise the painting, and how complicated it is.

“I began to think about all of these paintings as a mode of expression of our inner life. It’s not a political statement. It’s not a mode of communication. It’s not for you. It’s not for you [the viewer].”

You’ve mentioned a painting by Remedios Varo as a key reference. Could you share more about that?

Early in this process, Guillermo mentioned that his family had a work by Remedios Varo in their collection. She’s an incredible surrealist. He showed me this painting: a woman wrapped in her own hair, sitting at a table. There’s a hand reaching from behind. A cat made of leaves. A person upside down in a pot. Anything you want to see, you can see in that painting.

It’s very quintessentially surrealist, and it takes you into this dream state. I kept thinking about that figure at the table as a kind of starting point. [It’s] an imagined scene, but arguably, you can attribute it to her. It’s her inner world, her fantasy, her fears—being expressed in this really vivid way.

Artworks from The Olivia Collection, part of the exhibition Between Us. Curated by Diana Nawi. Photography by Andy Butler and Sergio López. Courtesy of The Olivia Foundation.

What does it mean for this exhibition to center women artists? Was that a conscious decision?

I was thinking a lot about this idea. The collection is primarily women, and what does that mean? Does that mean anything?

I began to think about all of these paintings as a mode of expression of our inner life. It’s not a political statement. It’s not a mode of communication. It’s not for you. It’s not for you [the viewer].

Some people think in images, some in words, some through their hands. It was really important to have a starting point that allowed me to mix types of work and scales of work in a single gallery—so that each inner world could unfold in its own way.

Woman in a Rowboat runs until September 28th at The Olivia Foundation. Open Wednesday to Sunday, 11AM – 6PM. Free entry, no reservation is required. If you would like to schedule a tour please contact us at info@oliviafoundation.mx